In Spring 2020 I worked remotely. I remember the first few weeks felt like a long,

uneasy snow day, or like a nap that ends after dark. I thought my apartment

would eventually start to feel small, but after the temporary lockdown turned

into indefinite isolation, the rooms began to expand. Hours of my day were

spent getting lost in old, familiar corners. I noticed the paint on the windowsill

in the kitchen was peeling and the grout in the bathroom was mildewy. These

discoveries made me anxious, not because they were particularly bad but because

I had never noticed them before. I started to watch my cat more often,

following her eyes to try to see what she was seeing. How many other things had

I missed? What if they were important?

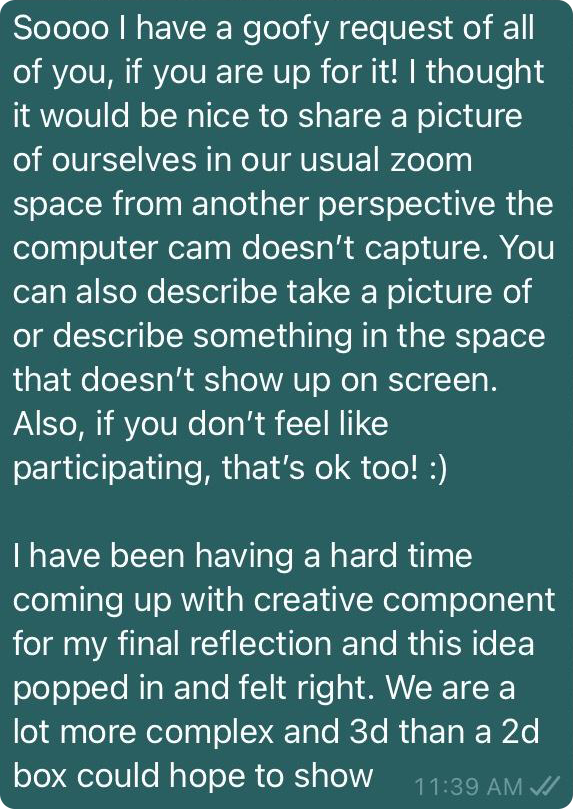

We began

school 6 months into lockdown. I had not had a meaningful social interaction

with a new person in a while and your tiny portraits were very meaningful

to me. As wonderful as our meetings were, remote learning felt incredibly

restrictive. Encased in tiny, pixelated rectangles, I struggled to access a

feeling of connectivity or control in the absence of physical togetherness.

![]()

When the newness of remote learning made the fuzzy transition into familiarity, I began to feel very small—both in the virtual classroom and in my

daily life. I started to worry my apartment wasn’t expanding, but I was

shrinking.

![]()

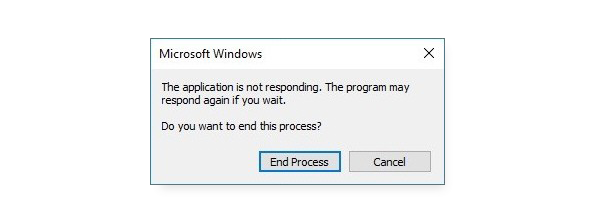

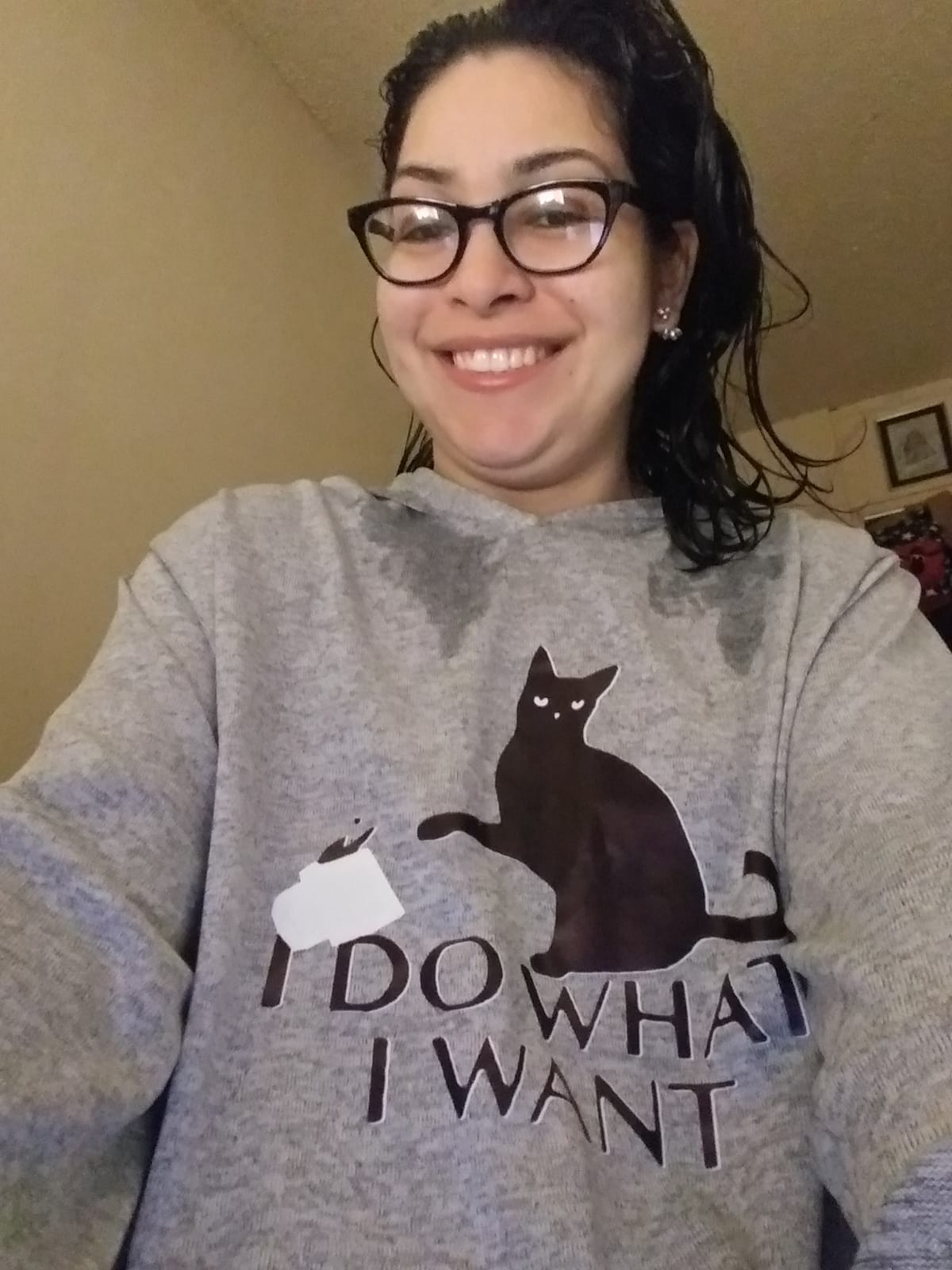

Talking

about theoretical frameworks in class reminded me of framing devices in general.

Once you look for them, they are everywhere—neighborhood blocks; bodega windows; bathroom mirrors; social media feeds. Though I was barely leaving my apartment,

I felt surveilled by the architecture and objects in my home. Most unsettling

was catching my reflection in a dark monitor. The black mirrors that seemed to

demand most of my attention framed an image of myself I didn’t recognize.

To gain

some sort of control over these contexts, I began to impose my own. I used my devices to capture the frames around me—digital screens, within tabs, within windows.

I even tried to draw our class...

This helped me feel a little better in the moment but didn’t offer any lasting relief. Documenting the frames around me felt like filming an unjust interaction on the subway: I had evidence that something had happened but no clear pathway to justice. I considered the possibility that my passive documentation of the thing that bothered me so much was not only unhelpful, but maybe making it worse.

Existing framing devices

often reinforce dominant systems of hierarchy and control in the absence of our intentional efforts to resist them. In

social work, how we understand and document service users has the potential to misrepresent them in

permanently harmful ways. While beginning to foster an awareness of how frameworks

can harm, my understanding of framing was itself incomplete.

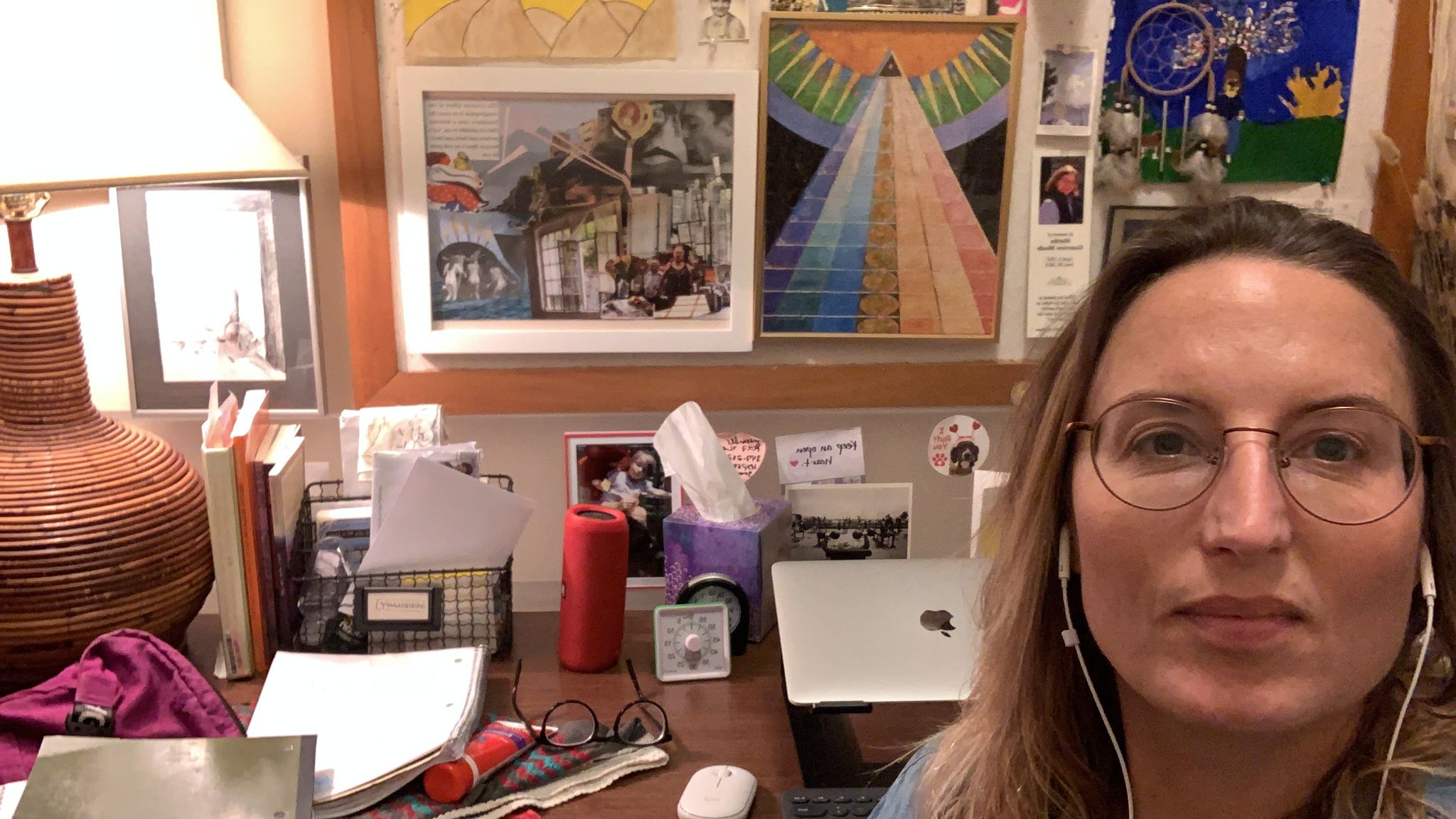

Things changed for me when our professor shared that she was pregnant. Her self-disclosure reminded me that the most

important parts of ourselves are often just beyond what is visible. While framing devices can oppress and reduce us, they can also enrich the meaning of our lives, expand our sense of possibility, and even support human life. Unlike the peeling

windowsills in my kitchen, this discovery absolved me of my need to see

everything all the time.

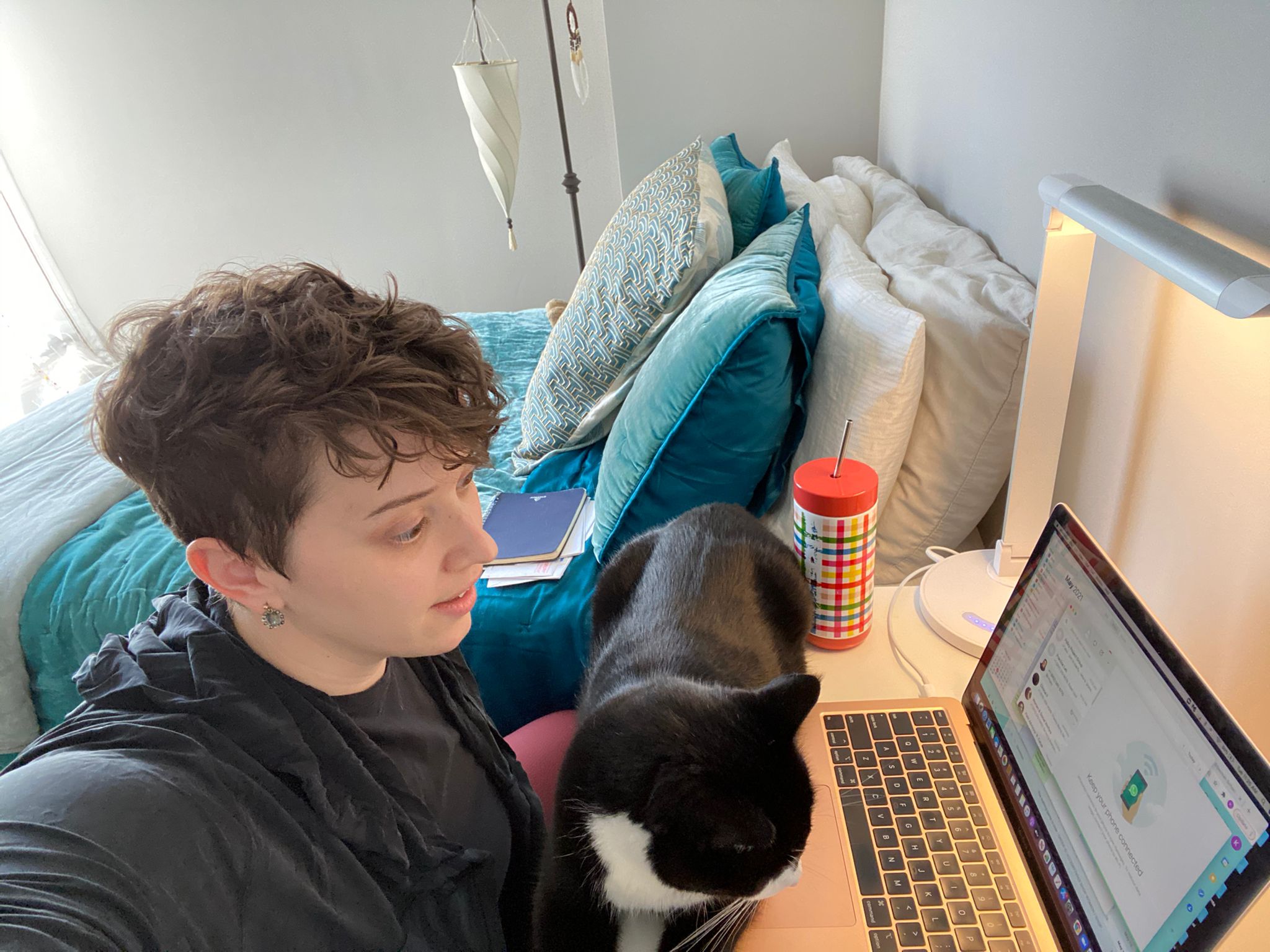

![]()

Human beings are wired for narrative and social connection. Because framing devices form the armature of story and our interactions, it is not possible to live outside of them. Though we don’t often get to choose the story format or how it will be received, we do have some control over what is captured. In many ways, choosing the content of a story is what social workers are asked to do for others, but what we see in isolation is rarely sufficent or equitable. While doing the deep, collective work of creating more equitable story formats, existing framing devices can be made liberatory when their subjects get to decide what parts of themselves are included in the frame. If we would like to offer meaningful advocacy and support to service users and our peers, we can construct thoughtful opportunities for them to show us who they are and how they would like to be represented.

![]()

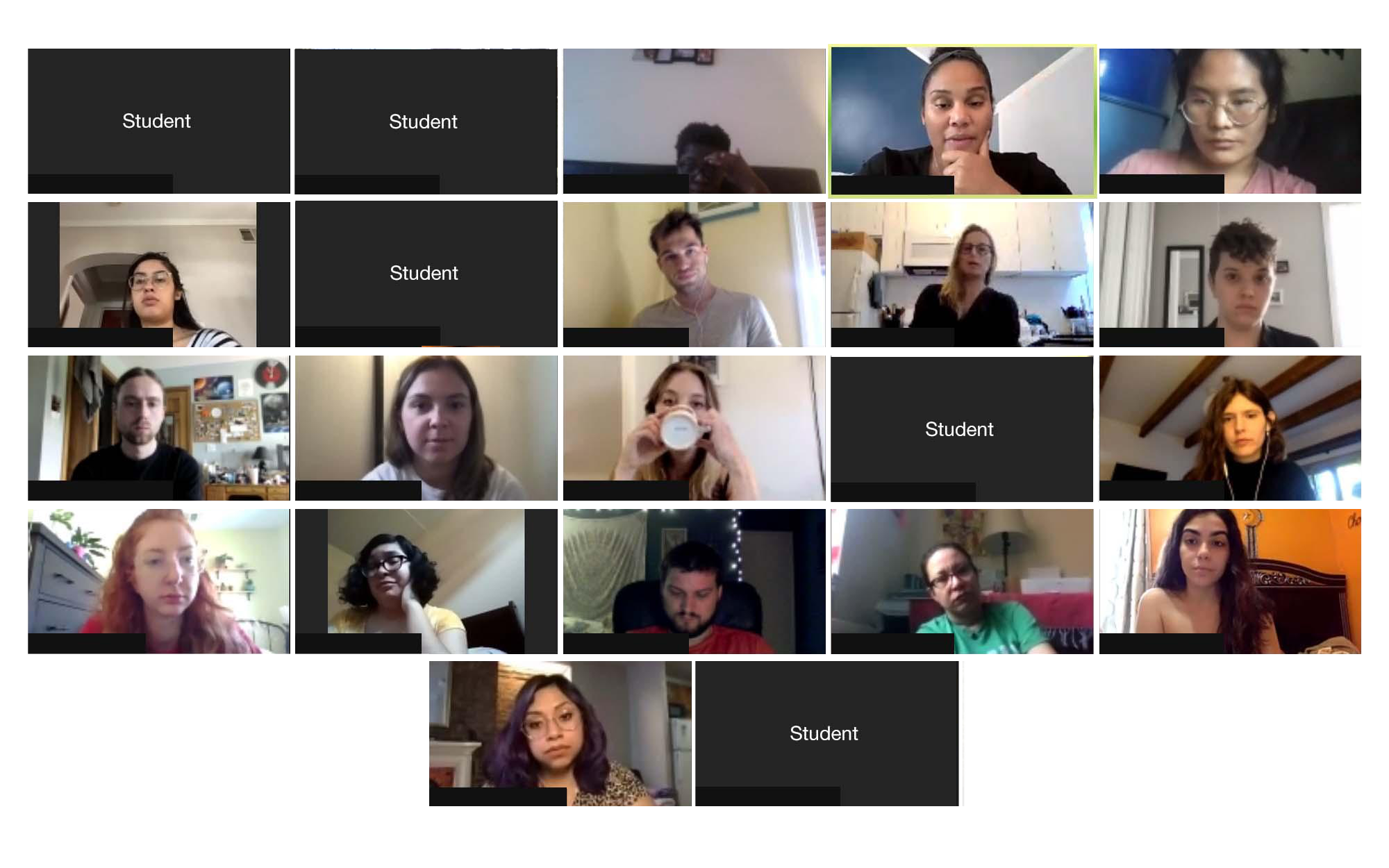

To my other virtual learning classmates: thank you for allowing me

to show you a little bit of me, and for sharing these parts of yourselves with us.

![]()